This week I’m resuming my history of CART’s IndyCar World Series.

A big factor in CART’s growth through the mid-eighties was the arrival of March Cars in IndyCar racing. Founded in 1969 by future FIA president Max Mosley and ex-McLaren designer Robin Herd, March had raced with some success in Formula 1 and established itself as one of the world’s leading production race car manufacturers before entering IndyCar racing in 1981.

By 1983, March had captured the majority of the IndyCar market and threatened to win the 1983 CART championship with both Tom Sneva driving for Bignotti-Cotter Racing and Teo Fabi with Forsythe Racing. Over the winter of 1983-84, March churned out more than forty new 84Cs as master salesman and designer Herd sold cars to fifteen teams, including A.J. Foyt and Pat Patrick.

Never one to go with the tide, veteran crew chief George Bignotti switched from running Marches to the new Theodore chassis at the end of 1983. But Bignotti was back in the March camp for 1984 with Colombian F1 driver Roberto Guerrero replacing Tom Sneva, who jumped fortuitously to the brand new Mayer Motor Racing team run by former McLaren men Teddy Mayer and Tyler Alexander.

Mayer and Alexander had been partners with Bruce McLaren since 1963. The pair had run the highly-successful McLaren Can-Am team in the sixties and equally powerful USAC team through the seventies. At the same time, they were key men in McLaren’s F1 team until Ron Dennis came along in 1980 with a Marlboro-backed buy-out plan.

By the end of 1982, Mayer and Alexander were out of McLaren and they put together a new March-equipped CART team for 1984 with Sneva and Howdy Holmes driving. Other top March drivers and teams included Bobby Rahal and Truesports, Fabi with Forsythe, Galles Racing with Al Unser Jr. and Tom Gloy, the Kraco team with Geoff Brabham and rookie Michael Andretti, and Patrick Racing with Gordon Johncock and Chip Ganassi.

Click here to talk to the team.

There was a brand new Lola too, called the T800, which was a vast improvement over the previous year’s car. The Lola T800 was designed by former Lotus engineer Nigel Bennett and it was an infinitely better car than the T700.

“Lola needed somebody who understood and believed in ground-effect and Nigel Bennett was that man,” Mario Andretti says.

“Nigel was part of the original ground-effect revolution at Lotus. He understood it. He was a well-rounded, solid guy.

“Nigel did a good job on that car. It was the first half-aluminium, half-carbon IndyCar and it was properly done with a good wind tunnel program.

“Nigel’s a really clever guy,” Mario adds.

“His demeanour is very professional, an unflappable type of guy. I always liked Nigel very much.

“He was responsible for reviving Lola and making Lola a viable customer car because after the T800, Lola was the benchmark. I give him a lot of credit.”

With the T800, Bennett pushed Lola into adopting modern, carbon fibre composite technology. At the time, not enough was known about carbon fibre’s ability to withstand high-speed impacts with a superspeedway’s walls so the central part of the chassis, or driver’s compartment, was a more traditional aluminium honeycomb ‘bathtub’. This was bonded to a complete carbon composite top section and nose that made the chassis much stiffer than the T700.

“We had done it at Ensign,” Bennett says.

“John Barnard had built the Formula 1 McLaren with an all-carbon tub, which was pretty revolutionary at the time. But there was no real crash-testing in those days. In fact, I don’t remember doing any crash-testing.

“So we were a bit nervous about how carbon would react in a shunt. We had a few shunts with the Ensign and they were alright, but they weren’t the sort of impacts you get at Indianapolis or any other superspeedway.

“So we stayed with an aluminium honeycomb structure for the bottom half of the monocoque and glued the carbon top onto it. We glued together the top half and bottom half in the same way people subsequently glued together carbon tubs. I can’t remember the exact figures but it was a pretty stiff chassis, which the previous Lola had not been.”

Aerodynamically, the T800 was infinitely better than the T700 although by today’s standards the wind tunnel work for the T800 was rudimentary.

“The wind tunnel program was alright, but it certainly wasn’t anything like they’ve developed in recent years,” Bennett says.

“It was a rolling road tunnel with a quarter-scale model. The models were better than anything we had at Ensign, but not very good with no real suspension members.

“The wind tunnel program was very disorganised. There wasn’t a wind tunnel team or anything like that. We used the Imperial College tunnel in London and Tony Cicale came over to most of the tests. Tony put in his feedback and that was very good.”

Beyond Newman/Haas, Lola’s only other customer in 1984 was veteran Formula Atlantic, Formula 5000 and sports car team owner Doug Shierson, who had moved up to CART in 1983 and hired Danny Sullivan to drive for him in 1984.

A Kentucky native, Sullivan had come up through FF1600 and Formula 3 in Europe, then raced Formula Atlantic in North America and the Can-Am before driving for the Tyrrell Formula 1 team in 1983. Shierson started the year with his own cars, but they weren’t up to the job and his team switched to Lolas during the month of May at Indianapolis.

The failure of the SCCA’s Can-Am and Formula 5000 road racing series had resulted in a flood of new drivers and teams coming into CART and by 1984 the Indy car series was booming.

The Can-Am’s demise also brought new road course and street races to CART, including Chris Pook’s Long Beach Grand Prix which had run an increasingly successful Formula One race from 1976-’83. But F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone demanded too much money from Pook for 1984 and Pook made the decision to switch to the burgeoning CART series.

In fact, Long Beach was the opening race of the 1984 season. Andretti dominated the first IndyCar race in Long Beach, winning from the pole, but he failed to finish at Phoenix while Sneva was third in Long Beach and won from the pole at Phoenix.

Meanwhile, Penske Racing had a tough start to the year. An all-new car, the PC12, and an all-new Ilmor/Chevrolet engine were designed and built for 1984, but car and engine performed poorly at Long Beach and Phoenix. Penske then made a decision to temporarily shelve his car-building program and buy a fleet of new Marches for Indianapolis and the rest of the season, like almost everyone else in the field.

Despite the heavy workload, Penske’s team was ready for Indianapolis where Rick Mears was on the pace all month and very happy with his car on both short sprints and long runs. Al Unser was a little less happy, but both of them ran plenty of miles during practice. Mears qualified third behind the pace-setting Mayer Motor Racing Marches driven by Sneva and Howdy Holmes while Unser qualified a solid tenth.

At the start of the 500, Mears jumped into the lead and led the early laps chased by Sneva, Mario Andretti, Fabi and Al Unser Jr., all of whom led the race for at least a handful of laps. But Andretti collided in the pits with rookie Josele Garza, unhappily ending his race, while Fabi and Unser Jr. also hit trouble. Fabi dropped out because of a broken fuel pump and Unser’s engine overheated because of a cracked water pipe.

The second half of the race was all about Mears and Sneva with Mears leading most of the time although Sneva was able to catch him and lead for a few laps with around a hundred and fifty miles to go. But Mears was able to retake the lead and on what turned out to be the race’s final restart with thirty-two laps to go, Sneva came coasting into the pits with a broken constant velocity driveshaft joint.

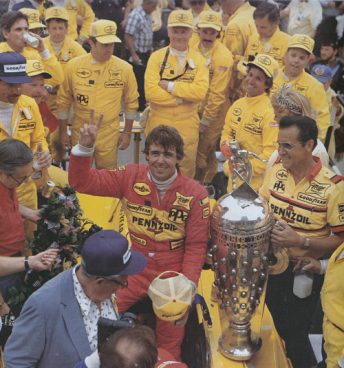

Mears drove home unchallenged, winning by two laps from Roberto Guerrero’s Bignotti-Cotter March and team-mate Al Unser Sr’s sister car.

“That was a satisfying win, not so much for the race because Sneva fell out at the end and at that point we had a pretty good lead,” Mears remarks.

“The satisfying part about that race was we showed the depth of the team and how strong the team was. We took the same equipment that most of those guys had been using for a couple of years and beat them at their own game.

“We got it turned around with very little practice, qualified on the front row and ended up winning the race. That was one of the things that made the second win even better than the first.”

Mears’s second win at Indianapolis put him in contention for the championship behind early point leaders Sneva and Andretti. Mario’s son Michael was also in the mix after making a solid start to his rookie CART season by finishing tenth at Long Beach. Michael followed that up with a strong third at Phoenix and an impressive fifth at Indianapolis.

But CART’s 1984 championship was taken by his father Mario who went on to win six races, take eight poles and lead 572 laps that year. It was a great year for the world-renowned veteran as he won his fourth IndyCar title and his first in 15 years.

“Mears and Sneva demonstrated at Indy and Milwaukee that we had fallen behind the Marches,” Andretti says. “But even when the Marches were at their best we were not far behind. We were never out of the ballpark and as the season went on we got a better and better handle on the car. More often than not, we were the team to beat.”

Mario scored a remarkable win in that year’s Michigan 500 after coming back from losing a lap because of problems with an errant spark plug wire. In the end he was able to lead the last 26 laps, holding off a relentless attack from Sneva who complained after the race that Andretti had unfairly blocked him.

But Sneva was never able to get alongside Andretti and finished a frustrated second with Mears third. Andretti was delighted to score his first oval win of the year and his first 500-mile win in 15 years since winning the Indy 500 in 1969.

“The Michigan 500 had to be the highlight of the oval races because we went against some pretty long odds,” Mario recalls.

“When we had the ignition problem, I lost a lap or more. Well, thank God for 500 miles and some great work by the team with the strategy and taking advantage of every possible situation that was available to us. We went unnoticed for much of the race and then boom! We were there.

“Not all the players were there at the end, but we beat Sneva and Mears, the guys we were racing for the championship. It was a good day for us and there was a pretty hard fight right to the end with Sneva.”

Andretti always believed Mears was the man to beat that year. After all, Mears and Penske had won the CART title three times in 1979, 1981 and 1982, and Al Unser added another title for Penske in 1983.

“I thought Mears was going to be my main competition, no question,” Andretti says. “I thought with both Rick himself, and the Penske team, there was more consistency than there was with Sneva, Rahal or Sullivan.”

But Mears’s season came to an abrupt end at the twelfth of that year’s sixteen races, a new event run at the tiny, seven-eighths of a mile Sanair tri-oval in Quebec’s Eastern Townships about 80 kilometres southeast of Montreal. Mears had tested at the track and was raring to go but just half an hour into the opening practice session he made a very uncharacteristic mistake.

“We had tested at Sanair and nobody else had, and that was part of my problem where I screwed up,” Mears recalls.

“We had an advantage starting the weekend because of our test that I wanted to try to keep. We were running around that little bull ring and it was hard to get a clean lap. I came up on traffic and I just got overanxious and stuck my nose where I shouldn’t have. That’s the bottom line.”

Mears ran into the back of Corrado Fabi’s car, bounced off Fabi’s car and plunged heavily into the line of guardrail separating pit lane from the front stretch. The nose of his car plowed beneath the bottom row of guardrail, tearing a retaining post out of the ground before scooting down the track, without most of its front bulkhead and pedal assembly. The wreckage clouted the guardrail one more time before coming to a stop.

Mears was slumped unconscious in the cockpit with his feet poking out of the car’s destroyed front end. Occurring directly in front of the pits, the collision scattered crewmen in all directions but as the dust settled many of them, Roger Penske included, rushed over to help CART’s safety team do its job.

Both of Mears’s feet were badly crushed in the accident. In fact, every one of the twenty-seven bones in his right foot were broken and both of Rick’s Achilles tendons were detached. He also had a concussion caused by a contusion at the back of his skull.

At the hospital in Montreal there was talk of amputating his badly damaged feet.

Roger Penske didn’t like what he heard or saw from the Canadian doctors and after consulting with CART medical director Dr. Steve Olvey, Penske decided to fly orthopaedic surgeon Dr. Terry Trammell from Indianapolis to Montreal to provide a second opinion.

Trammell and Olvey were colleagues at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis and Trammell had done superb work earlier in the year to save and repair both Danny Ongais’s and Gordon Johncock’s broken legs.

Olvey strongly recommended Trammell to Penske, who responded immediately by flying Trammell to Montreal on his Lear jet, then flying Mears to Indianapolis for surgery after a day of stabilisation in Montreal.

Mears was out of action for nine months as he went through a series of surgeries followed by a long and difficult rehabilitation program.

During 1983 and 1984, Bobby Rahal and Truesports were beginning to come on strong while Danny Sullivan proved how good the Lola T800 was by winning three races in 1984 for Doug Shierson’s team with the first customer T800.

Sullivan’s trio of wins showed that a customer team could win with a T800 and helped launch Lola’s attack on March’s dominance of CART’s car market.

Sullivan’s performances with Shierson also convinced Penske to hire him to partner Unser in all the races in 1985 while holding a third car for the recovering Mears to drive in selected races.

Discussion about this post