Thirty-eight years ago this week on March 11, 1979 CART ran its first race at the one-mile Phoenix International Raceway. It was the start of an exciting new era in American motor sport that ultimately unraveled a quarter of a century later amid a sad display of the worst human failings.

Championship Auto Racing Teams was formed in the fall of 1978 by Roger Penske, Pat Patrick, Dan Gurney, A.J. Foyt, Jim Hall, Teddy Mayer and Tyler Alexander for McLaren, plus Bob Fletcher and Jerry O’Connell. The team owners originally intended to act as a collective bargaining group to pressure the United States Auto Club and race promoters to raise the level of prize money, TV coverage and commercial sponsorship as well as taking a more pragmatic and knowledgeable view of Indy car racing’s technical and engine rules.

As winter arrived the team owners decided they couldn’t work with USAC and would run their own series in 1979. Back then, prize money averaged between only $80,000-$100,000 for most races and the Indy 500 paid a grand total of just $1.2 million with $300,000 going to the winner. Other than Indy, TV coverage was nonexistent, nor was there a series sponsor to help promote and market the sport. CART aimed to change all that and also bring some stability to the engine and car rules to help make a very expensive sport more cost-effective.

Bobby Unser qualified his brand new Penske PC7 on the pole ahead of Tom Sneva’s Sugaripe Prune McLaren (owned by Jerry O’Connell), Johnny Rutherford’s factory McLaren, Danny Ongais’s Interscope Parnelli and Rick Mears in a Penske PC6.

Twenty-one cars took the green flag and Unser dominated the early laps with the new ground-effect PC7 but his car’s handling deteriorated and he fell back. Ongais took the lead only to blow an engine, allowing Gordon Johncock to forge ahead and collect $18,670 for winning the race. Johncock beat Mears, Sneva and Al Unser while Bobby Unser made it home a lap down in fifth place ahead of Mike Mosley’s Eagle and Wally Dallenbach’s Wildcat.

CART’s first year played in front of small to middling crowds with few, if any, high-profile venues and not much depth in teams. But it was much better than USAC’s rival seven-race 1979 championship. In an attempt to encourage smaller teams with Chevy stock-block engines to compete, USAC cut its boost limit from 80 to 50 inches and CART followed suit. A.J. Foyt easily won the USAC title against minimal competition driving primarily his Parnelli-Cosworth 6C. He also ran one of his Coyote-Foyt/Fords one last time at Texas in 1979 and won.

Click here to talk to the team.

But from the beginning, the owners tended to squabble among themselves. A few months before the 1979 season began Foyt deserted CART and rejoined USAC, becoming a persistent critic of CART. Foyt won five of USAC’s separate series of seven races in 1979, breezing to the last of his record seven USAC titles. It was also USAC’s last season sanctioning Indy car races. In 1980, the two organizations briefly formed a combined Championship Racing League but the CRL partnership fell apart before the year was out and CART took off entirely on its own with USAC remaining as the sanctioning body for the Indy 500.

Meanwhile, Dan Gurney and many others believe CART stumbled from the moment it left the starting gate in 1979 because of a poor TV contract. CART decided to buy its TV space in a ‘time buy’ rather than earning an all-important rights fee, which is the lifeblood for all professional and most amateur sports. But TV producer Don Ohlmeyer convinced the team owners that a ‘time buy’ would provide CART with a strong income stream from selling their own advertising space and also give them production and editorial control of the TV shows. Almost forty years later the longterm effects of CART’s essential failure to establish and develop a proper TV package hangs like a millstone around IndyCar’s neck.

“I think the first major mistake CART made was when they established the first television contract,” Gurney says. “I felt the TV contract was going to be the most important element of this new organization that was being put in place. I couldn’t see how others could miss that point. It seemed obvious to me, but Don Ohlmeyer sold them on the ‘time buy’ thing. There was no effort that I was aware of to extract serious television money from the networks even though other sports/entertainment businesses were already doing that very successfully. I thought that was a gigantic mistake. I think at that point they dropped the ball enormously.”

In its first year CART staged thirteen races at six tracks–Phoenix, Atlanta, Trenton, Michigan, Watkins Glen and the Ontario Motor Speedway. Three of the races were double-headers and the new series raced twice at Phoenix, Atlanta, Trenton and Michigan. CART’s first race drew nineteen teams, all single-car operations save Penske and Patrick’s two-car teams. In stark contrast to today, there were no fewer than seven different car builders–Penske, McLaren, Lola, Eagle, Parnelli, Wildcat and Lightning–and three different engine types–Cosworth DFX, Offenhauser and the DGS/Offenhauser developed by Sonny Meyer for Patrick’s team.

Without doubt, those were very different times with many teams building their own cars or engines. A thriving racing industry in California and Indianapolis supplied Indy car teams with parts and compnents. Only a few years earlier the Penske and Parnelli teams competed in F1 for a short time. Back then, American race teams were respected around the world. Mario Andretti was the defending F1 World Champion with Team Lotus and Indy car racing enjoyed a great roster of established stars including Foyt, Andretti, the Unser brothers, Johnny Rutherford, Gordon Johncock, Tom Sneva and Danny Ongais.

But the 1979 season belonged to Rick Mears an exciting new star from California who won his first Indy 500 and two CART races to take CART’s inaugural championship in his second of fifteen years with Penske Racing. Teammate Bobby Unser won six races but failed to finish too many times and was beaten to the title on consistency, a Mears trademark. Johncock finished third in the championship ahead of Rutherford and Al Unser.

Penske hired Mears as his third driver in 1978. Mears drove Mario Andretti’s cars in the races where Andretti was otherwise occupied chasing the World Championship with Lotus in Formula 1. Penske also ran Mears in a third car in the 500-mile races at Indianapolis, Pocono and California. Mears came through to win three USAC races in 1978 at Milwaukee, Atlanta and Brands Hatch.

The young California off-road racer was cool, handsome and personable as well as clearly being an exceptionally gifted driver so it was no surprise when Penske decided to fire Sneva at the end of 1978 and promote Mears to a full-time ride. Penske also hired veteran Bobby Unser to be the team’s lead and test driver, thus beginning a new era of domination for Penske’s team.

From 1979 through 1981 Penske ran two cars for Unser and Mears with Mario Andretti driving a third car in some races in 1979 and ’80. Over those three years the team won no fewer than 21 races, including two Indy 500s. Mears won the Indy 500 for the first time in 1979 and two other races to take his first of three championships in four years. Unser won six races in 1979, four in 1980 and the Indy 500 (after a long dispute) in ’81, but he was unable to win the championship.

Prior to the month of May in 1979, Roger Penske wasn’t convinced that the new ground-effect PC7 was the way to go for the 500. Unser had done 4,000 miles of testing with the PC7 and was totally committed to racing the new car.

“Roger gave me the option,” Mears recalls. “He came to me and said, ‘I know Bobby’s been doing most of the R&D on the new car. Which car would you be more comfortable with? It’s your choice. You can run whichever car you want.’ I was more familiar with the PC6, so I made the decision to stay with the 6.”

It turned out to be a good choice because Mears was quick all month and qualified on the pole for the first of a record six times he would take pole at Indianapolis. Sneva qualified Jerry O’Connell’s McLaren M24 second with Al Unser third fastest in the brand new Chaparral 2K. Bobby Unser qualified the PC7 fourth ahead of Phoenix winner Johncock’s PC6 with A.J. Foyt qualifying his Parnelli sixth.

Of course, CART’s leading teams had to fight a legal battle before they were allowed to enter their garages and start practicing for the 1979 500. At the beginning of the month USAC informed each of Penske, Patrick, Dan Gurney, McLaren, Jim Hall, Jerry O’Connell and Bob Fletcher that they were ‘not in good standing with USAC’ and their entries were therefore denied. They had to spend a few days in federal court in downtown Indianapolis appealing their case before a judge ruled that USAC had to accept their entries.

The first half of the 1979 500 was dominated by Al Unser and the new Chaparral. Al had driven a year-old Lola in the opening races of the season before the Chaparral arrived in Indianapolis for its public unveiling. Dubbed ‘The Yellow Submarine’, the Chaparral 2K was designed by John Barnard and built in the UK by BS Fabrications. The car set a new standard for ground-effect design and Unser was in command of the 500 until his transmission broke just after half-distance.

After the Chaparral dropped out, Al’s brother Bobby took over in the PC7 with Mears tailing him closely, confident that he had the car to challenge and beat his more experienced teammate at the end of the race. But with twenty laps to go Unser’s top gear broke and he had to nurse the car home in third gear. Rick swept through to take the lead and drive home to win the 500 in only his second start in the race. Foyt was a distant second, almost a lap behind.

Mears drove a PC6 at Trenton two weeks later in a pair of 100-mile sprint races. He finished fifth and seventh while Unser won both Trenton races in his PC7. At the next race on the high-banked Michigan Speedway, both Unser and Mears drove PC7s. Unser qualified on the pole and led the race but failed to finish while Mears qualified fifth and finished fourth behind Johncock’s Patrick PC6, Mike Mosley’s Eagle and Rutherford’s McLaren. Mears reverted to a PC6 for the last time at the Watkins Glen road race in August where Unser and he finished one-two for Penske. Back in a PC7 for the next race at Trenton, Mears turned the tables, beating Unser across the line in another Penske one-two sweep.

For the California 500 in September, CART’s team owners pulled out all stops to produce a full field. Mario Andretti flew in to drive a third PC7 for Penske in his only CART race of the year and Rick’s brother Roger was also in the field, driving a third Patrick Racing PC6. The race was swept by the Penske team with Unser winning from Mears and Andretti. By that stage the inaugural CART championship was strictly an intra-team battle between Unser and Mears.

Unser kept the contest alive by winning at Michigan two weeks later with Mears third behind Sneva. Mears all but wrapped-up the title with an excellent win at Atlanta at the end of September. Unser finished third at Atlanta behind Johncock so Mears enjoyed a 280-point lead going into the year’s final race with a maximum of 300 points available.

At CART’s season-closer in Phoenix, Al Unser finally scored the Chaparral’s first victory while Bobby Unser and Mears finished second and third so Mears rounded-out a superb sophomore season with Penske by taking his first CART title from Bobby Unser, Johncock and Rutherford.

“The main thing that sticks out to me about that year–and it actually started standing out more to me later on down the road–is that I didn’t really appreciate it,” Rick remarks. “I didn’t realize what it was and what it meant. It was almost like we were supposed to be there. That was the feeling, and it would have been very disappointing if we weren’t. It was almost like I expected to do this and I didn’t appreciate how difficult it was.

“Everything had happened very quickly from off-road to Super Vee and the stuff with Simpson. It was kind of a fairy tale story. It was like, ‘That’s the way it’s supposed to work.’ I didn’t understand it then, but as time goes on and looking back on it later, you begin to realize.”

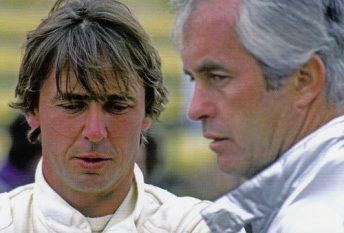

Rick learned a tremendous amount that year from his irascible teammate Bobby Unser.

“He had his own views but he didn’t let them out too much!” Rick chuckles. “He taught me more than he knows. He taught me how to read between the lines. He taught me how to sort through the BS. He taught me how to keep my eyes and ears open. I had my own pride and if he didn’t want to tell me, I didn’t want to ask him either. That way, if I beat him, I had done it on my own terms. It was more satisfying to me to do it that way. So I learned how to watch, listen and act like I wasn’t doing those things, and read between the lines.

“Watching how Bobby did things and came to certain conclusions was a lot of fun. Anytime I’d make a change of my own in the direction that he had already gone, he’d say, ‘Oh, that won’t work.’ He tended to try to steer me one way, or the other, even as far as not wanting me in the car in testing so I wouldn’t get as many miles. But it was fun. I enjoyed it and we had a good time working together. Part of the fun in working with him was figuring all that out. He sped-up my learning curve.

“Bobby and I are good friends,” Rick adds. “He’s a great guy and a real character, and he taught me a lot. It was fun to compete with him. He definitely worked on chassis and setup, which is what I enjoyed. He always felt like if he didn’t have a ten percent advantage he was five percent behind. That’s the way he looked at it and that’s why he won a lot of races.”

Discussion about this post