Engine performance has long been a bone of contention and has been brought back into focus following the completion of off-season category wind tunnel testing and a minor centre of gravity change in recent weeks, not to mention a lopsided set of results at Hidden Valley last month.

Supercars’ existing engine parity regime relies on the metrics of Accumulated Engine Power (AEP) and Engine Power Weighted Average (EPWA), which are a legacy of the five-litre pushrod engines which propelled most to all of the field for 30 years.

While there were several engine builders at any given time during that period, the task of achieving parity is undoubtedly harder now than it was when the championship featured only Fords and Holdens because of the differing architecture and displacement of Gen3 engines.

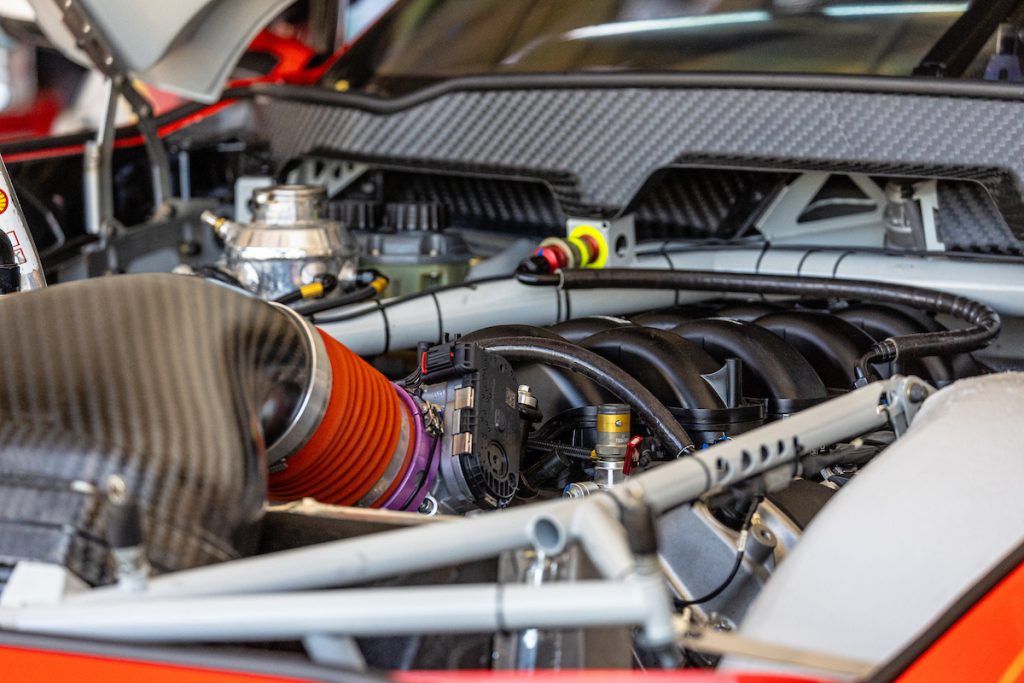

That the Ford Mustang is powered by a 5.4-litre quad cam engine – an unusually undersquare one at that – and the Chevrolet Camaro by a 5.7-litre pushrod raises questions as to whether they accelerate differently.

Ironically, while the Mustangs were consistently slower in the speed trap when this year’s season-opener took place at Mount Panorama, new Ford engine supplier Dick Johnson Racing is said to have been forced to install a smaller air restrictor to ensure it does not breach the AEP cap.

However, according to independent engine expert Pete Wallace, Supercars should do away with restrictors as a means of trying to achieve parity.

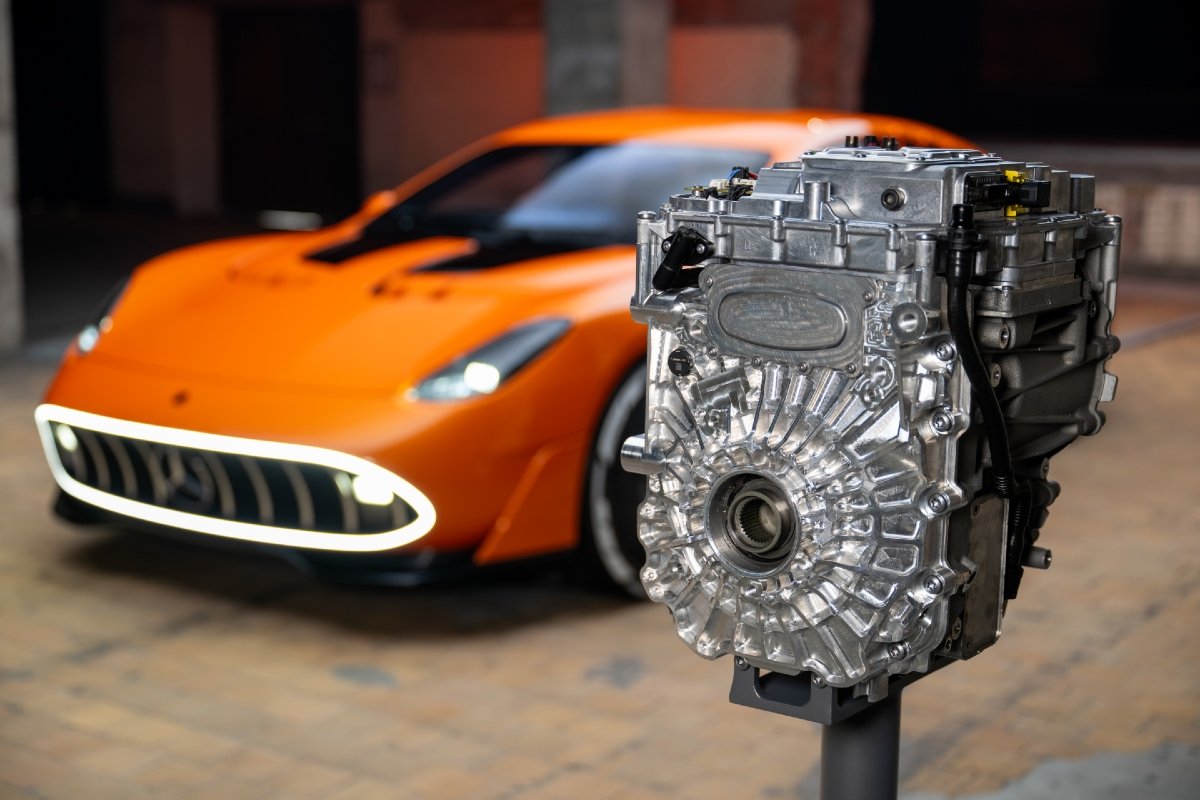

The solution, he says, already exists, thanks to the fly-by-wire throttle which is standard across the field under Gen3 regulations.

Instead of the accelerator pedal being physically connected to the engine with a cable, movement of the pedal triggers an electronic signal which opens the butterfly.

Wallace, who was Stone Brothers Racing’s engine builder from the mid-2000s into the 2010s, says Supercars can map the throttles so that torque output is equal throughout the rev range.

“The throttle pedal position gets set at 10 percent increments from zero, and then the engines are made to be the same,” he explained to Speedcafe.

“Whether one’s eight percent [butterfly opening] and one’s 10 percent, but as long as the torque number’s the same, all the way through. No restrictor.

“Then, at 100 percent [pedal], one might be 100 percent [butterfly] and the other one might be 80 percent, 85 percent, 90 percent… I don’t know.

“That will change throughout the rev range. One engine versus the other might be at a hundred percent at 4000 revs and the other engine is at 92 percent at 4000 revs, then it could be opposite at 5000 revs, and so on and so on through the rev range.

“Through the range, they won’t [necessarily] be the same.”

In summary, the butterfly is mapped versus the throttle pedal map throughout the rev range, to make torque equal.

The problem with using a restrictor is that it is a fixed, physical object and hence cannot be tailored to compensate for the differences from one engine to another through the rev range and throttle position.

“They’d be looking for acceleration [on the transient dyno],” said Wallace.

“They would also be looking for parity, which means ‘equal’, and, at the moment, I don’t think they’re equal because of the restrictor.

“The restrictor only works at 100 percent throttle, so at every other throttle position, both engines are different.

“It could be that one is better early on in the revs and that changes partway through and then that changes back again – that’s acceleration, and that’s out of the corner.

“On paper, a 5.7 versus a 5.4 would be hard to get the same, but not if you use fly-by-wire, that they mandated.

“If you had used an accelerator cable, you would have to use the restrictor, but if you use the restrictor, it needs to be calculated so the exit angle is seven degrees; no wider.

“In the size of the things that I’ve seen in Gen3, earlier on, that would have been at least 350mm long on the exit to the butterfly, and then what would happen is, the throttle response would be better and that’s because the recovery of pressure in the plenum would be faster with the seven-degree exit angle.

“But, as I said, you don’t need that restrictor; you just need to set both engines up, throttle on the dyno at 10 percent, equal torque on both engines no matter what percentage they need; 20 percent throttle at the dyno; and so on up to 100 percent, and both engines with the same torque no matter what throttle or revs they need.”

According to Wallace, fuel consumption would be even closer, and hence there would be no need to revert to using compulsory pit stops as a parity measure in the enduros, a rule which was already scrapped last year.

Engines have already been shipped to the United States for transient dyno testing, with a set-up phase to take place after this weekend’s NTI Townsville 500.

Discussion about this post