Supercars livery season is a frantic three-week stretch during which teams rapid-fire release their colours for the new campaign.

Some are uncovered at in-person launch events while others go straight to the internet.

All are instantly judged by fans, who take to social media to share strong opinions on the latest changes or lament the lack thereof.

So what happens behind the curtain of this annual Supercars beauty contest? How do the cars end up looking the way they do? And who’s involved?

To find out we asked one of the paddock’s most prominent livery designers, Peter Hughes, who has played the V8 livery game since joining Holden as a designer 35 years ago.

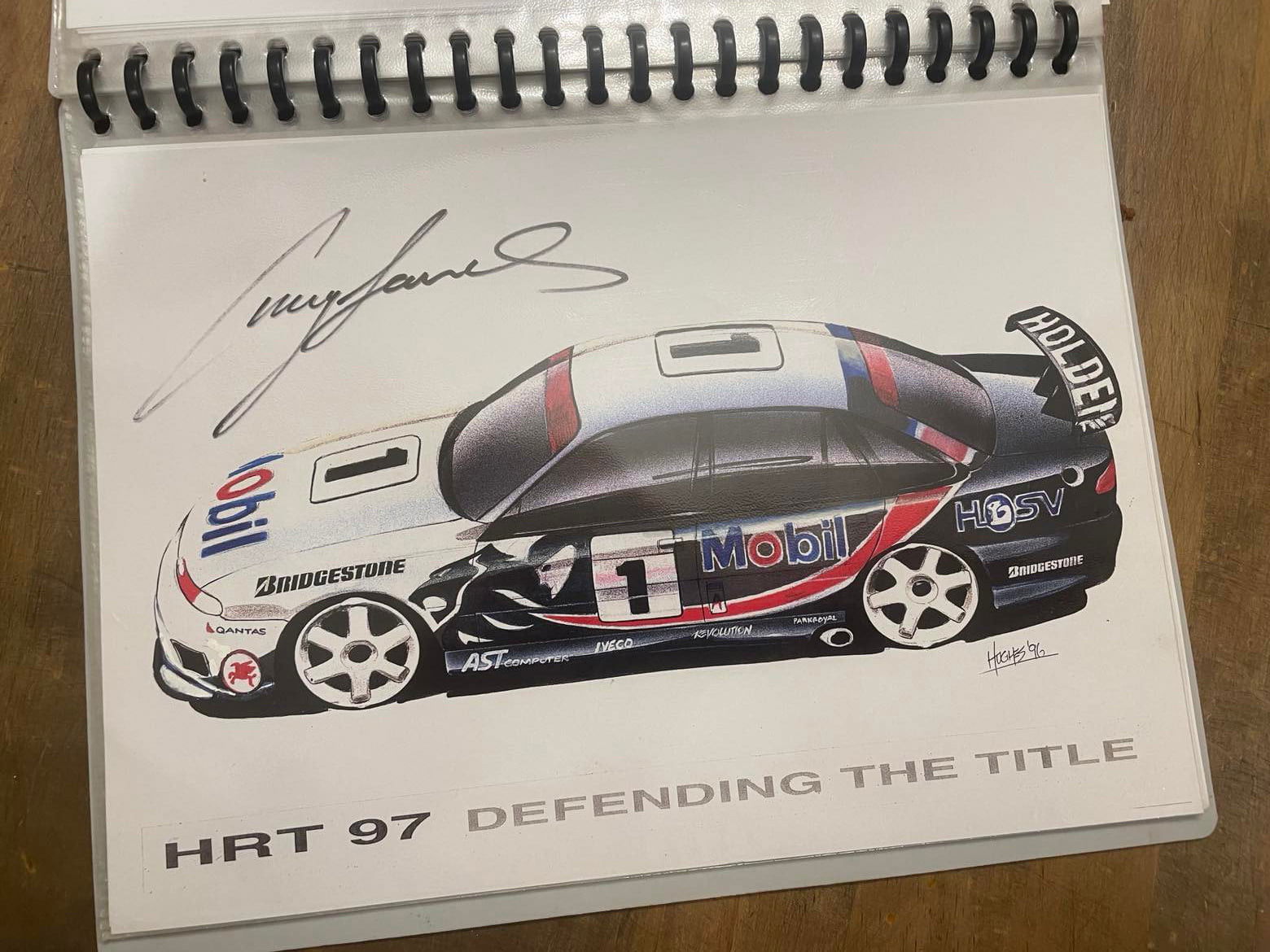

That role led to sporadic involvement in Holden Racing Team liveries during the 1990s. His first full car was the 1997 machine made famous by Peter Brock’s full-time farewell.

Hughes became a Holden Motor Sport fixture from 2006, designing the HRT car – among others – each season, before adding Triple Eight to his roster when Red Bull joined in 2013.

Fast-forward to today and, with Holden no longer in existence, Hughes’ relationships with Triple Eight and Walkinshaw endure as part of his status as a freelancer.

The Blanchard Racing Team cars are Hughes’ work too, while he was also contracted to put the finishing touches on Grove Racing’s Penrite livery designed by a third party.

“Every team and every sponsor is different, so you need to be really flexible,” Hughes tells Speedcafe of the secret to Supercars livery success.

“The objective at the start is always to make the car look great and stand out, but you’ve also got to make sure all the partners are happy and, somehow, link them all together so it looks cohesive.

“That’s basically the brief for every modern race car.”

The role of the livery designer has therefore evolved with the commercial realities of the sport.

Rewind 30 years and almost every leading team had a single sponsor – usually a cigarette or oil brand – that commanded the whole car.

Even 20 years ago when Hughes became a regular on the scene, the top teams like HRT had it far easier than today.

“It was really easy to hit the brief when Holden owned 80 percent of the car,” he says.

“I could basically do whatever I wanted. I’d put the lion on the hood and the side, blend it all together, add a couple of little sponsors and job done. The cars looked fabulous.

“If you move to say the current factory car for Chevrolet, which is Triple Eight, it’s not so easy. There are three or four big brands on that car and some very tight restrictions on presentation.”

The sheer number of brands packed onto the cars nowadays leaves little room for any design at all.

“The livery itself used to be perhaps 40 percent of the car and the signage 60 percent. Now the signage is 90 percent and the livery is almost token,” says Hughes.

“They are predominately one colour without much room for stripes or fancy dot fades or things like that. Those elements take up space on the cars that the teams can sell.

“That’s very challenging from an artistic point of view.”

Red Bull is world-famous for being ultra-restrictive with the use of its brand.

The caused headaches when Holden moved its HRT backing to Triple Eight in 2017. A lion was never going to be allowed to sit alongside a bull on the same car.

But the issue of managing different objectives of major sponsors is not unique to Triple Eight, it’s universal. The modern Walkinshaw cars are another strong case in point.

“A company like Truck Assist might want to do something really funky and bright orange, but you’ve also got to work with Mobil who have been there for 30 years and need to be respected,” he explains.

“You’ve got two worlds crashing together. And then at Walkinshaw you’ve also got two cars that need to look similar from a design point of view but with different colours…”

While livery designers typically work with the commercial manager of each team as their primary contact, Hughes says taking a passive approach does not result in the best outcome.

“Yes, you sit at the computer and do the design, but a modern livery designer should be negotiating and persuading people as they go,” he said.

“It’s not just a phone call or asking the team to do it, I will actually go to the garages and meet the commercial managers of the brands and build the relationships.

“Part of the new role of a livery designer is being a negotiator.”

All challenges considered, it’s in some ways amazing there’s any changes year-on-year if a team is carrying over the same sponsors. So where does the drive for a new design come from?

“I push pretty hard every year on all teams, and a lot of the times I will present something purposefully pretty wild and out there just to get people engaged,” Hughes says.

“The response is almost always that they want something like that, but it doesn’t meet all the brand guidelines. But if they like the concept, we can tone it down and tweak it from there.”

While Hughes’ first car in 1997 was designed with markers and pencils, the modern cars take shape via computer programs such as Photoshop or Illustrator and 3D CAD models.

“I’ll flip from one to the other,” says Hughes. “I’ll have an idea, create a quick side-view in 2D in Photoshop, get it onto the car in 3D and see what to adjust back in Photoshop.

“When you’re presenting to a team these days, having a CAD model that can spin around with the whole livery on it means you can make really concise decisions about every corner of the car.”

How long the whole process takes also depends very much on the team. Some are fully sorted before Christmas, while others are still locking down sponsors into the New Year.

Key elements of the livery are often then used in decorating other items such as the team transporter, pit walling, team kit and more, which must all be done before the season starts.

For Hughes, the creative process of livery design never stops.

“Pretty well the week after they’re launched, I’m already thinking of ideas that I’m going to float for the next year. That’s my job,” he says.

“I don’t wait for the team to come to me. For Triple Eight in particular, I’m very proactive in putting together what I think it could be and should be.

“It might come back to almost what it was the year before, but it doesn’t mean we don’t do our due diligence and try things to see if the sponsors will move forward with us.”

So what is it like seeing your latest designs come to life each year?

“There’s lots of frustration when you see the cars and they’re not exactly how you want them,” he says.

“But if I had my way, all the cars would be really complicated. They would be running really expensive wraps and chrome and God knows what, and they’d be a nightmare to maintain and repair.

“Sometimes you’ve got to take your designer hat off to help the team and the sponsors get to the end result. You must be a help, not a hindrance.

“It may not be exactly how you wanted it, but over the years I’ve learned to live with that.”

The fan reactions are also something the designers must live with. Hughes says a lot of the harsher comments are simply based on the tribal nature of the Ford vs GM fanbase.

“It’s healthy, in a way, that there is still that heavy commitment to the sport and the brands,” he says.

‘The fans make the sport and hooking into the liveries when they come out each year is part of the game. That really doesn’t faze me in the slightest. The last thing I’d do is take it personally.”

While modern technology allows anyone to be an amateur livery designer, there are only a handful involved throughout the entire Supercars grid.

It’s a privilege Hughes does not take for granted.

“I think holistically, the way Supercars go about it, and how much effort the teams put in every year, we’re one of the best presented categories in the world,” he says.

“Every time our 24 cars hit the grid, they all look great and I’m proud of being part of making sure our Australian series looks world class.”

Hughes shares his artwork through his popular Facebook group, Peter Hughes Motorsport Art & Design, and sells prints of modern and classic race cars through hughesmotorsportart.com.

Discussion about this post