Speedcafe.com continues to attack coronavirus isolation this week by running a series of extracts from the autobiography of the site’s founder, Brett “Crusher” Murray.

The remaining 100 copies of the book are being sold at a discount of $40 (inc Express Post) with 100% of proceeds going to Speedcafe.com’s charity, Motor Racing Ministries. To buy your copy CLICK HERE.

The book does have a more serious side and in this chapter “Crusher” looks at some of the lowest days that motorsport has dished out.

Chapter 19 of 29: Motor racing is dangerous

On almost every motor racing ticket that is purchased around the world, there is a disclaimer which starts with the simple words ‘Motor racing is dangerous’.

While it is meant as some sort of disclaimer for the fans, sometimes you are jolted back into reality to how true that statement really is and how we lull ourselves into a false sense of security.

Motor racing can be as boring as hell, but even on those occasions, the unexpected can happen in the blink of an eye or an ill-turned wheel when suddenly the dynamics change dramatically.

In extreme cases, the ultimate sacrifice is paid and your world and that of everyone around you changes forever.

I have put this chapter together as a small tribute to some terrific blokes, and also to give an idea of what needs to happen when it all goes wrong.

Obviously car, equipment, and track safety have improved dramatically over the years.

We are certainly a far cry from the early speedway days when a driver would look to the left and then the right while taking a piss before a race and know that one of those dudes standing next to him would not be around at the end of the night.

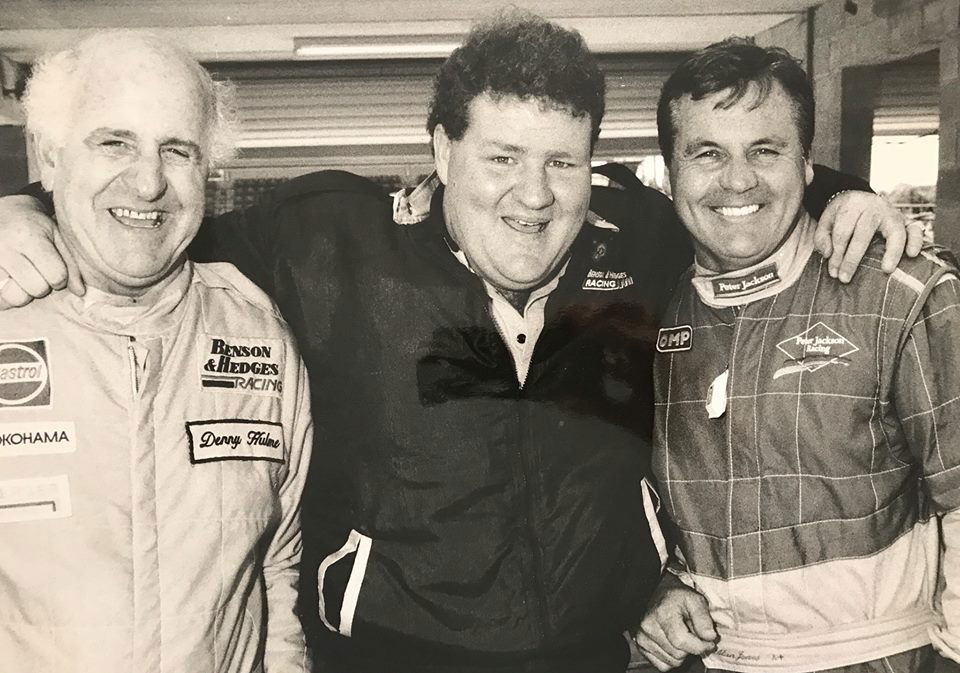

My first real experience of how punishing motorsport can be came at Bathurst in 1992, when Kiwi legend Denny Hulme died at the wheel of one of the E30 Benson & Hedges BMWs, which he was sharing with my good mate Paul Morris.

I was the media manager for the team and was one of the few media types who had managed to get under Hulme’s guard.

In fact, he was known as ‘The Bear’ because of his grumpiness towards reporters, but he always had an enormous amount of time for me, despite the fact I was born in the same year as his 1967 World Formula One Championship.

Each year Denny would wait for me to roll out my next lot of Kiwi jokes as we sat around the team dinner table.

While Denny’s death came as the result of a heart attack and not an accident, his loss had a massive effect on our team and the broader motorsport community.

It was my first taste of tragedy in the sport and I floundered my way through all the responsibilities, many of which I had never even taken into consideration before.

I remember handing the media release to our Team Manager Frank Gardner in pitlane and him just welling up and handing it back to me with a blank stare and simple nod of approval.

They had been good mates for years and had both survived an era in the sport when death was common and chiselled a different type of toughness into a generation.

Just as I turned from Frank, I was met by Jimmy Stone, who had left the B&H team to join his brother Ross at Dick Johnson Racing.

Jimmy worked with Denny at McLaren in Can-Am and F1 and was one of a couple of mechanics at the test where Bruce McLaren was killed in a testing accident at Goodwood in 1970.

In fact, Denny was supposed to test the car that fatal day, but had burned his hands in an accident preparing for the Indianapolis 500.

Jimmy had come down to our pit to find out what was going on, hearing rumours floating up and down pitlane. I handed him the release and life just drained from his face.

It is only now, 25 years later and older, that I look back on that moment and understand the level of emotion I was oblivious to back then.

Amazingly, Denny was just the second driver to die in the Bathurst 1000 after Sydney privateer Mike Burgmann crashed into a tyre barrier at the base of the bridge on the high-speed Conrod Straight in 1986.

A large three-corner chicane named ‘The Chase’ was designed into the track the following year to reduce speeds. Ironically, it was at this part of the track where Don Watson lost his life in 1994.

Five months later we were on the ground at Phillip Island in Victoria for a round of the Super Touring Championship when Gregg Hansford was killed in his Ford Mondeo after it hit a tyre bundle at turn one and bounced back onto the track and into a path of Mark Adderton’s Peugeot.

Hansford was one of the few competitors in the world who had made a successful transition from two wheels to four. He competed very successfully on the world 250cc and 350cc stage before turning to touring cars, winning the 1993 Bathurst 1000 with Larry Perkins and the 1994 Bathurst 12-hour with Neil Crompton.

As the enormity of the situation unfolded I was called in to offer some advice and provide a bit of direction by series management. I also had my own young driver in the field, Steve Ellery, who had to be consoled as emotion and rumour spread throughout the paddock, with the race having obviously been red-flagged.

This incident showed how totally inadequately prepared the Confederation of Australian Motor Sports (CAMS) was for such a situation.

As I was helping prepare a statement, Hansford’s good mate and my fellow Gold Coaster, Charlie O’Brien, came into the room looking for answers.

The pair of them had finished second in 1993 Bathurst 12-hour.

Charlie pulled me aside and just looked at me for an answer.

I said only three words to him. “He’s gone mate.” Charlie slumped into a chair and bawled like a small child.

Meanwhile, helicopters were already in the air, flown out by newsrooms in Melbourne, bringing journalists who would be looking for the story.

I had prepared a statement and suggested we call a media conference, once the choppers had landed, to get the reporters all in one place.

It was vital that we controlled the situation, but the CAMS representative was determined to go with a ‘no comment’ policy.

The following conversation either enhanced or damaged my reputation for political correctness, depending on how you look at.

Basically I told the representative that he was a ‘f#^!ing idiot’ and that he was minutes away from his organisation becoming a bigger laughing stock than it was already perceived in the marketplace.

I suggested he take some advice and be a part of the rollout, or just “get out of the f#^!ing way”.

CAMS looked at its policy after this, but it was not until I did some more direct work with them in 2007 that any clear direction was developed for such instances.

When you have a death in the sport there are just so many elements that need to be considered.

In this instance, one of the major priorities was Gregg’s two sons Ryan and Rhys, who were 12 and nine at the time, and his second wife Caroline, who was nursing their eight-month-old son Harrison.

Ironically, Hansford’s former brother-in-law, Bruce Allison, who had gone to high school with Gregg and who was a gun in Formula 5000 in his own right, has become a good mate of mine and shares a regular Friday afternoon beer.

I attended an IndyCar test with Bruce at Firebird International Raceway in Phoenix, Arizona in 1991, as he attempted to put together a deal to race at the Gold Coast IndyCar event the following year.

Unfortunately, some last-minute sponsorship drama put an end to that.

In 1999 Trudi (my wife) and I headed to the final round of the Champ Car Series at Fontana in California.

It was a weekend that should have been one of the highlights of my career for many reasons, but turned out to be one of the worst.

Two weeks earlier Dario Franchitti had won the Gold Coast race and taken the lead in the championship from Juan Pablo Montoya and the plan was to celebrate his title and the fact that I had signed my contract that weekend to work with Bruce McCaw’s PacWest organisation the following season.

On lap nine of the race it all came undone with a horrific crash that instantly claimed the life of my good mate Greg Moore.

The Canadian was just 24 and was competing in his last race for Forsythe Racing before joining the mighty Penske organisation and had been pencilled in to become a superstar of the sport.

Sadly, he was the second driver in three races to be lost in the championship after Gonzalo Rodriguez was killed in a practice crash at Laguna Seca.

A day earlier Greg had been knocked off his scooter in the paddock area after a collision with a delivery van.

It happened right outside the PacWest hospitality area and I was one of a couple of people to go to his aid.

He broke his hand in the incident and could not participate in qualifying, but started the race from the rear of the field with the help of a hand brace and pain-killing injections.

There is an unwritten rule in the sport about drivers creating too much of a bond with each other.

It is a reality of the commercial ‘dog-eat-dog’ nature of the business, but also rolls back to the earlier days of the sport when death was just accepted as a regular part of the industry.

Moore had become part of a quartet including Franchitti, Tony Kanaan and Max Papis, who had become known as the Rat Pack and much of the group’s notoriety was created under my watch on their annual trip to the Gold Coast.

I was sitting in the Fontana pitlane a little numb from the whole accident when I looked up to see the flags in the main straight at half-mast and that’s how I learned we had lost him.

Incredibly the drivers were also noticing the flags, despite their speeds of 380kmh-plus, because they would use them as a reference point for the wind on the main straight.

Dario had a drama in his last pitstop which saw him finish the championship on equal points to Montoya, but he lost the title on a countback and good friend Adrian Fernandez won the race.

But all of that was to mean nothing.

A couple of hours after the race we arrived at Rossa’s Italian restaurant where we met Champ Car chaplain Father Phil, who we invited to join us for dinner.

Jan Magnussen, who had run a few races with Patrick Racing in the lead up to Fontana after losing his F1 ride the year before, also joined us. During the night Magnussen received a phone call to say that his seven-year-old son Kevin had just won his first go-kart race back in Europe.

Father Phil said grace and a prayer for Greg. I made a speech and a toast to Greg after we ate.

I said it was obviously a day that we would never forget, but we needed to try and salvage some sort of positive from it.

I suggested we should remember it as the day that Kevin won his first race and that one day we would hopefully be toasting a similar result for him in F1.

In 2014 I recounted that story when Kevin finished second in his F1 debut in Australia for McLaren Mercedes and I rang Jan who was competing in the Sebring 12-hour sports car race in Florida to recount that ’99 dinner, which he remembered fondly.

In 2003 I walked into the track for the Gold Coast Champ Car race only to get a call to say that Tony Renna had been killed in an off-season tyre test at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Tony had been one of my drivers in Indy Lights at PacWest in 2000 and finished fifth in the title chase behind teammate Scott Dixon, who clinched the championship.

Ironically, Tony had signed a deal to join Scott at Ganassi Racing in the Indy Racing League the following season.

Tony was a hell of a kid and Trudi had developed a relationship with him through the 2000 season, running the PacWest hospitality.

His death really knocked her around and the emotion of this day reinforced my thoughts of “Once you’re my driver, you’re always my driver”.

Obviously the death of Peter Brock in 2006 was one of the biggest news stories to happen in the history of Australian motorsport.

I had more to do with the nine-time winner later in his career and actually promoted his ‘retirement’ race at Bathurst 1997, which was seen as the first real breakaway event in the on-going war with the Super Touring fraternity in Australia.

The entire build-up to that event was amazing and probably took my understanding of the Brock phenomenon, and his relationship with the fans, to a whole new level.

When Ayrton Senna was killed in 1994 I remember being numb for a couple of days, but I couldn’t work out why, considering I had never known him.

It got to a point where I actually took the time to sit down and analyse my state of mind and I put it down to the fact that if the greatest driver we have known could die at the wheel, then the guys I was dealing with on a daily basis were a lot more vulnerable than I had considered.

It was a similar feeling when Brock hit a tree in a tarmac rally in Western Australia.

I remember getting a call from someone on the ground in WA about the accident and I went straight into PR mode to work with my drivers who were obviously going to need some emotional and strategic support.

It was the night before Trudi’s birthday and we had a party planned at home. I remember just heading into the bedroom after a massive day of media commitments, sitting exhausted on the end of the bed and crying uncontrollably before gathering myself up and heading out to the party.

I knew I had maybe been in this game too long just a month after Brock’s death when I almost went into autopilot after a serious incident at Bathurst.

Kiwi Mark Porter was involved in a crash at the top of Mount Panorama after his stationary car was hit by an Optima Sport Commodore driven by David Clark in a Supercars Development Series race on Friday.

Optima Sport was a client of BAM Media and was looked after by one of my improving young guns Lee Hanatschek who joined me as a raw rookie and has since developed into one of the hardest working and most creative PR managers in the business.

Porter was transferred by air to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney while Clark was airlifted to the Nepean Hospital with significant injuries and was placed into an induced coma with multiple fractures and a punctured lung.

In these situations the team PR/Media Manager becomes not only the contact for the team, but in many cases is left to deal with worried and grieving family, police, doctors, fans, sponsors, and the media, many of whom have never previously had anything to do with the sport or its culture.

In this case we had to take care of most of those things and the best place for Lee to be was at the hospital. Magnifying the situation was the fact that Lee was Clark’s brother-in-law.

It is the little things that you learn from these situations that you can not be taught at university.

On the Saturday morning the national papers were full of stories about the accident and Lee delivered them to the room at the family’s request. But before he arrived he removed as many of the graphic stories and images as he could.

There was just no need for them to see them.

The level of responsibility went up a notch when Porter, who had his wife, young son, and parents by his side, passed away on the Sunday.

From a management point of view we had to reorganise the next month of commitments and also consider the emotional state of Lee, who was on a massive learning curve, whether he knew it or not.

I am sure it is a month he would rather forget, but he knows it helped him develop into the operator he is today.

All the advice and experience that I provided to Lee was called upon in spades in the early hours of Monday, October 17, 2011.

I was sitting in my Gold Coast office watching the last race of the Indy Racing League season at Las Vegas when there was a 15-car crash on lap 13, with some cars flying 100 metres into the air.

There were several drivers in that race who were heading to the Gold Coast the following day to compete in a unique international Supercars co-drivers race.

I had helped formulate it in an effort to keep an international theme to the event which was important for the Queensland State Government after A1GP bailed.

I was watching the race with a couple of my staff so we could pump out some stories that would give us some good solid exposure and bring the fans up to date early in our race week.

All that changed when a couple of wheels touched on the approach to turn two and basically destroyed half the field.

We did a quick summary of the situation to work out how many drivers who were to do ‘double-duty’ on the Gold Coast were involved.

It all went to another level when I got a phone call directly from the Las Vegas pitlane from a good friend and series insider, who told me English driver Dan Wheldon had passed.

I rang the Gold Coast event boss Tony Cochrane and advised him of the situation, suggesting that he keep everything ‘tight’ until there was official confirmation.

In the meantime, I did an assessment of who was injured and who would definitely not be making the trip, as well as a list of drivers who might not be in good shape emotionally.

I also made a list of possible tweaks to the international driver rules which had been set for the Gold Coast race and what drivers would be contenders given those changes.

We convened a management meeting at Supercars’ head office where I provided an update and went through all the scenarios, before getting the new strategy approved.

In the meantime, I had also been in contact with James Courtney and Marino Franchitti, Dario’s brother, who had come into the Gold Coast early in preparation for the event.

Both these lads were mates of Dan’s and had called me within minutes of the crash asking for updates.

Not only did I have to ring them back and tell them of Dan’s passing, I had to extend an invitation to a media conference at noon where we would confirm their mate’s death and advise everyone of the changes that would be made for the following weekend.

Although they are both mates of mine, there was certainly no obligation for them to do anything, especially given the personal emotion involved, but they showed up and were also a terrific personal support for me.

The reality was I had to ensure, as quickly and confidently as possible, that everyone knew the show would be continuing.

I had to put my personal emotions in a little storage area in the back of my brain for at least the next six days.

At the same time I was dealing with personal enquiries from people who knew Dan was a good mate, while also worrying about people like Dario, who I knew would be doing it much tougher.

As well as Dan, we would also be missing Will Power and Tony Kanaan from the original international line-up and they would be replaced respectively by Darren Turner, Richard Lyons and Allan Simonsen, the latter of which we would lose at Le Mans two years later.

By the time we got to the weekend, we had also established a trophy in Dan’s honour to be awarded to the leading international driver for the weekend, which was won by Sebastien Bourdais.

There is no doubt that the week was one of the toughest of my career and called upon every bit of knowledge and experience I had hoarded away during 25-odd years.

It was only a few months earlier I was in Dan’s pit and then back in his garage after he had won the Indy 100th anniversary Indianapolis 500. He signed the event program for me – “To the C#%t, now get me a ride in Surfers” – which we did.

Dan was the fifth Indy 500 winner to die in the same year as their race victory, tragically joining Gaston Chevrolet (1920), Joe Boyer (1924), Ray Keech (1929) and George Robson (1946).

I had T-shirts made in Dan’s honour and handed them out at our Speedcafe.com Greenroom After Party on the Sunday night.

That little storage area in the back of my brain, which is one of the most valuable assets a person can have in this industry, was unlocked around midnight, as was the second bottle of Jack Daniel’s.

In 2015 IndyCar racing claimed another great guy in Justin Wilson after he was struck by a piece of debris from a crashed car at Pocono Raceway.

Wilson, who at 193 cm was unusually tall for a driver, was always good for a decent sit-down chat and the last time we had one of those was the IndyCar presentation dinner for Will Power in Los Angeles the previous year.

I got to know the Englishman through four Champ Car appearances on the Gold Coast, but it was his last in 2007 which holds the fondest memories.

The Gold Coast event was heading into its 17th year and there had never been a repeat winner which was a record for a major international motorsport event. It has become a bit of an in-joke that I had one particular ‘repeat winner’ story I would roll out every year and just add the victor from the previous event.

Frenchman Sebastien Bourdais won the Gold Coast race in 2005 with Newman/Haas Racing, giving him the second of four consecutive championships.

Bourdais led the race from a fast-finishing Wilson in the dying stages of the 2007 event and held his position to the chequered flag.

Wilson came into the post-race media conference and walked over to me with a big smile on his face before giving me a hug.

“I am sorry Crush,” he whispered.

“All I could think for those last few laps is that Crusher is going to kill me if I don’t catch this guy.”

The following is the copy I provided for the book Lionheart, which was a tribute book to Dan Wheldon, written by well-known and respected English journalist Andy Hallbery and US scribe Jeff Olsen.

I was honoured to be able to make a contribution to what really is a terrific tribute to a terrific bloke:

I knew of Dan when he did Indy Lights with PacWest in 2002, as he joined the team the year after I left to return to Australia. I had an emotional connection with him in that his 2005 win was called by Andretti Green’s team manager John Anderson – the guy who recruited me to the United States at the end of 1999.

‘Ando’ was a great mate of mine, and he’d been robbed of an Indy 500 win with the Paul Tracy deal in 2002, so I reached out to DW the night of his 2005 win, congratulated and thanked him for winning the race for Ando.

With that I really got to know him socially and developed a proper mateship with him. We just hit it off and had this great relationship. I guess because he’s English and I’m Australian we had a similar sense of humour in a lot of ways. We used to take the piss out of him about his teeth but, you know, nothing was ever an issue. I think we both had a great respect for each other.

We’d call each other names that really can’t be repeated or printed here. That’s just how we were though. If we texted or called each other, that’s what we called each other. I’ve still got the last message he sent me. He even signed my 2011 Indy 500 program that way… and telling me to get him a V8 Supercar ride at Surfers. Which, we made happen.

Dan was supposed to be racing the Gold Coast 600 Surfers Paradise V8 Supercar race the week after Las Vegas with James Courtney for HRT, one of the most famous teams in Australia. The next part of the story is the bit we don’t like to talk about. That was certainly one of the worst weeks of my life.

We sort of battled through, I guess. The worst thing was we didn’t have a chance to grieve really because everything was happening. We put all our efforts into making it the best event we could but at the same time remembering and respecting Dan and his family.

We had little tributes done. We had special helmets and stickers made and the trophy for the highest ranked International driver at the event was named after Dan. When we got to the Sunday night after the race, it was like uncorking the bottle. All the emotions came out as we tipped our hats to him.

When Dario [Franchitti] won Indy the following year, that really meant something, you know?

That day was just amazing; seeing the entire crowd wearing the white glasses in tribute to Dan. I can tell you that night was one huge celebration with all the clan from Scotland. I’d just got to bed the following morning when Dario rang to see if I wanted to get my photo taken with him.

So I jumped straight back out of bed and went down to the track. They were packing up when I got there but Dario made them put everything back. That photo of Dario and me in the white-rimmed glasses with the Borg Warner trophy is one of the most special photos I’ve ever been involved in.

TOMORROW: It’s our bloody money

2009 provided one of the biggest challenges of ”Crusher’s” career after the no-show of the A1GP cars for the GC 600 – How was the event saved? – find out in tomorrow’s final extract.

Discussion about this post