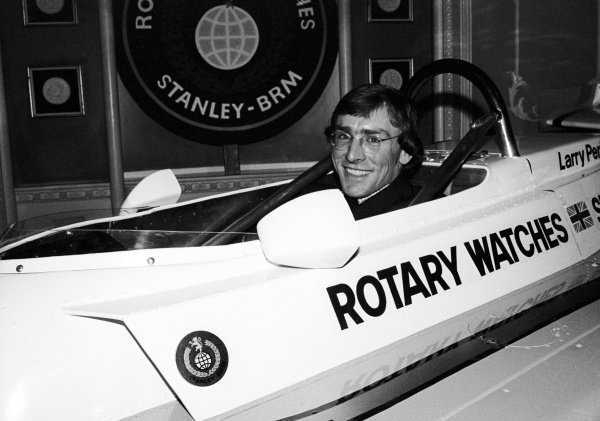

It could be argued that Larry Perkins is the fastest windmill mechanic on the planet. Or perhaps the fastest water borer, or fencer.

During his racing career he enjoyed huge success, conquering the Supercheap Auto Bathurst 1000 on six occasions. But the modest son of a World War II Air Force mechanic is just as accomplished with a spanner.

Perkins grew up on a remote farm in Cowangie where his formative years were spent learning off his father, Eddie – himself an accomplished racer.

From an early age motorsport beckoned him, and in 1970 he landed a job as a mechanic with Harry Firth at the Holden Dealer Team.

“I had been on the farm and wanting to go racing,” Perkins recalled to Speedcafe.com.

“I bought the English Autosport at the time, I used to buy that religiously, and I got to understand how racing worked.

“The first thing you had to do as a driver, if you wanted to be a driver, you better display your skill to someone who owns race cars.

“I bought a Formula Vee, a second-hand one, and relatively quickly there was three or four months, I started winning a lot of races.

“That put me into Formula Ford, and by then I won the Formula Ford championship.

“I had known Harry vaguely. My dad knew him from around the show trials and so on, so I wasn’t like a total outsider, and Harry offered me a job to drive a third car every now and again, and be a mechanic there.

“I didn’t have enough money to go to Europe, which I had won that trip, so I worked for a year to save some money.”

Victory in the Formula Ford Championship came with a trip to Europe, and the potential to embark on an international racing career.

For Perkins, that experience had to wait as he worked for Firth, fine tuning the mechanical trade he’d picked up throughout his childhood from his father.

“My dad did his apprenticeship when he was young, his motor mechanic apprenticeship in the ’30s and then he joined the air force when World War II broke out when he was 22, and he did four years in the Air Force as an aircraft fitter and so on.

“When dad came home from the war, we only had a relatively small farm and dad used to meet the demand by all the various local farmers to fix their machinery whether it be truck, tractor, harvester, and mostly out in the field.

“I happened to accompany dad sometimes on holidays, weekends or whatever, and we had a shed at home where dad would just get machinery in to fix, and so my life was totally exposed to mechanicing and fixing things in the field.”

Aside from his father’s tutelage there was no formal training for Perkins, which was further refined when he started at HDT in 1970.

“I put the very first V8 engine into a Torana, that was the number one prototype, that was my job,” he explained.

“Ian (Tate) was my boss. Frank Lowndes was actually in the road side of Harry Firth’s thing. I wasn’t in the road side, I was in the race side.

“Harry was a very practical operator, and he wasn’t too full of friggin academic.

“Ian Tate was another guy who didn’t waffle on and carry on, he was absolute hands-on, do the job, this is the job.

“He would understand what it is, and it all fitted-in very much with all my 14 years, 15 years of training before that, where attention to detail, be logical in how you prepare something, but attention to detail was always at the forefront of my preparation.”

After a year with Firth and HDT, Perkins headed to Europe to chase his dream of racing in Formula 1.

He got there too, though in cars and with teams that masked his talent. In 1974 he raced for Chris Amon’s squad, before it ran out of money and folded.

The following year was spent in Formula 3 and saw him win the European Formula 3 Championship.

“I did my own engines and chassis and everything out of the back of my truck,” Perkins said.

“We just did it our way, because we had no money to do it any other way.

“It was relatively successful. We toured Europe and won a lot of races.”

Back in Formula 1 the following year, his mechanical prowess was rather less useful though did afford him a unique insight into the way teams operated.

“By getting ultimately into Formula 1, I found there was no room to be a mechanic at all,” he reasoned.

“I quickly learnt in my two or three years in some dud Formula 1 teams and dud mechanics, that I’ve got to prepare my own stuff, because I want get success.

“I learned a lot, for instance in my first Formula 1 team was Chris Amon and Chris had a tremendously good designer called Gordon Fowell who was unknown in the world of car racing, but he was an absolute leader of the designers over there.

“I worked very closely with him and learnt a lot off him.

“A very high-level design that he put into our particular Formula 1 car, which is to say, no one in the world knows about it except me and him, and he’s now passed on.

“I learnt a lot of more detailed design and preparation based on design to achieve the end goal, which is try to have a fast race car.”

When the Formula 1 dream ultimately petered out, Perkins returned to Australia.

He continued racing and enjoyed success in Formula 5000 and the Australian Rallycross championship, before teaming up with Peter Brock in 1982.

“He approached me to be his co-driver and I said, ‘Peter, I’m not real fussed about co-driving’ because I was still specifically suffering from not making it in Formula 1, if you know what I mean? That was my only goal,” he recounted.

“I said, ‘Look, your workshops are bloody absolute shit show. I wouldn’t mind a run on that if that suited.’

“So that’s how we ended up. I ran his race workshop and co-drove when he needed a co-driver. The co-driver bit was second to running the scene.”

Part 2 of Speedcafe.com’s Mechanics’ Week feature with Larry Perkins follows this afternoon.

Discussion about this post